Milford Middle School to preserve name

The Milford School District is amid a strategic development plan, including the rebuild of a school that has been shuttered since 2013.

-

-

Homeless Bill of Rights pulled from Delaware House committee's Wednesday agenda

DOVER — As lawmakers prepared to return from their two-week spring recess on Monday, the Bill of Rights for Individuals Experiencing …

-

-

-

Delaware's June Jam CEO, founder Hartley dead at 68

Bob Hartley, CEO and president of the June Jam charity music festival, died in his sleep Sunday.

-

-

-

Sussex County Council reverses previous zoning denial

In August 2023, County Council voted 3-2 to deny a conditional use application for a solar farm south of Frankford but reversed course Tuesday …

-

-

DOVER — This is the time of the year when Miles the Monster’s heart starts to beat a little louder and his pulse begins to race. While the NASCAR Cup Series competes at Talladega …

View this issue of The Delaware State News or browse other issues.

Disclosure

-

-

Rothstein: We want your Opinion for the Greater Dover Independent

I am Benjamin Rothstein, and you have probably seen my name pop up all over the Greater Dover Independent.

-

-

-

Lewis: Solutions needed after rash of shootings in Dover

As one of your Dover City Council members and chair of the Safety Advisory and Transportation Committee, I felt compelled to publicly express …

-

-

-

Goduti: Kennedy left vision for peace unfinished

Less than a week after her husband’s assassination in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, Jackie Kennedy granted an interview with esteemed political …

-

-

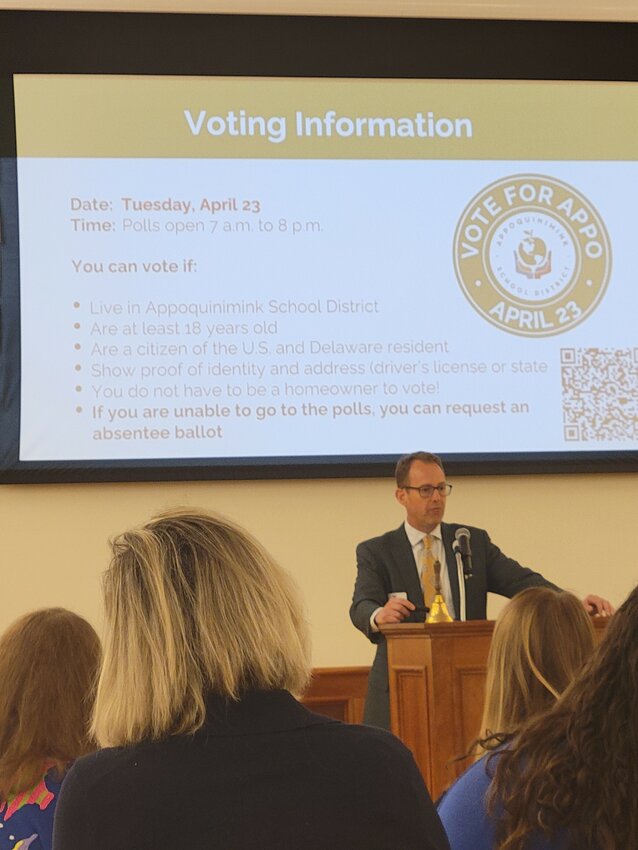

Middletown Area Chamber of Commerce holds spring luncheon

The Middletown Area Chamber of Commerce Spring Luncheon was held Wednesday at Middletown Memorial Hall.

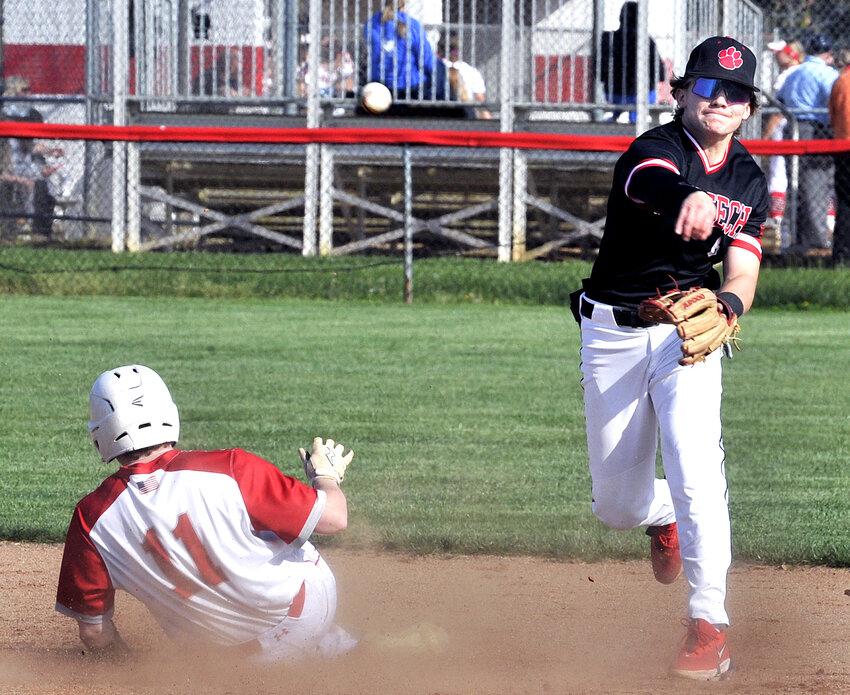

Photo gallery: Polytech vs. Smyrna baseball

Thursday's Downstate Delaware high school scores

College notes: Delaware State basketball team loses another standout but adds three transfers

Downstate Delaware high school scores

Harrington Raceway harness racing results

More Sports